Original Innocence

I have no idea where this one was going, but I'm trying to get back into the writing groove and this seems to be top of my mind.

There's a minority of people alive at this time that like it or not have much of their thinking shaped by the ideas of Christianity. A lasting legacy of the death-bed conversion of Constantine the Great who himself lived almost his entire life as a pagan of questionable devotion.

But that's basically why, if you're of European descent, or descended from the collonized of the British. You know a lot about Christianity and very very little about say: Zoroastranism, or Pythagoreans... Constantine's offspring basically made it a legal requirement for European citizens to be Christian, something that wasn't really relaxed until the enlightenment though eased a little in the Renaissance.

But that's going too far forward. First you have Augustine who conceived of the idea of original sin, which was highly influential on Thomas Aquinas - and this became a shaper of thoughts of all the societies that trace lineage back to the Roman Empire.

Such that I, raised by non-believers, in a secular society give some credence to the idea that I was born broken, in deficit, indebted and need to do something in the course of my life to make myself whole. That I am under some obligation to do something with my good fortune because it was gifted to me and I am not worthy of it.

I'm sure this takes many manifestations, but to me original sin in the modern material world really manifests as the need to live up to our potential. To make the most of our opportunities. That if we rest on our haunches and simply say 'enough' then that makes a waste of our lives. It makes us bad people.

Now there's a place for religion in cultivating ourselves. And how I feel it should be navigated particularly by people like me, who cannot abide the bullshit of deriving moral authority from extraordinary claims, is another post. Richer in my experience are psychology - the understanding of the mind, and practical philosophy - what constitutes a good life.

Much of the work of clinical psychology is, I believe, having to deal with original sin. Specifically that children being egocentric in behavior, internalize and blame themselves for the dysfunctions of their caregivers. There are a lot of adults that believe they failed to make their parents happy, or they failed to save their parents marriage. And it is true some adults have a child in an attempt to save a marriage, or even more children to save a marriage, but the fault lies with that adult, not the child.

Again it's hard to draw distinct defined edges around concepts as fuzzy as religion, philosophy and psychology. They all feed into each other. But I once had a councilor break the therapeutic process down for me into two steps:

1. Look for Patterns.

2. Relieve Tension.

Let's look at that second part. Because it's a part that original sin can contribute to. What is the tension? The 'tension' most often is betwixt our conception of who we are supposed to be, and who we are. Incredibly productive people berate themselves for feeling tired, or taking breaks, or taking days off, or holidays etc. Nice people beat themselves up for viewing pornography. Devoted partners hate themselves for feeling attracted to people who aren't their partners.

There are ample opportunities to beat ourselves up for perceived flaws.

Hopefully you can relate to this notion of tension. Let's now turn to the notion of relieving it - Carl Rogers, one of the nicest people in the history of psychotherapy whom along with Maslow was one of the first to take psychotherapy from simply correcting for pathos (negative) psychology but look at trying to attain the pinnacle of psychological health.

Maslow called this pinnacle 'Self-actualization' the ability to be oneself. Rogers called it 'Congruence' basically a freedom from the psychological pain of cognitive dissonance. And perhaps earliest of all was Jung who called it 'Integration' specifically 'Integrating the shadow'.

Even then, there's an argument to be made that Nietzsche in the school of philosophy who said 'become what thou art' coined the notion of a pinnacle of psychological health. In turn perhaps owing that to Plato, fanboy of Socretes, to whom the unobserved life was not worth living.

I've digressed, let's get back to Jung. Jungian archetypes, 'Analytical Psychology' is I will admit, off-putting for most. It often descends into psychotherapuetic quackery. You wouldn't believe how many times I've been enjoying a youtube talk by a professional psychologist on shadow work and suddenly they start talking astrology and specific advice for star-signs like that's a perfectly reasonable given.

So if you dare to tread the archetypical road, expect deterrants in the form of outright idiocy. But the basic mechanics of Jung's concept of the Shadow are perfectly reasonable and functional, even independantly verifiable. Perhaps best captured in the sensible words of one of histories great level-headed imperfect human beings Abraham Lincoln 'You can please some people some of the time, and some people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can't please all of the people all of the time." and if you can't draw the connection, it's just a fundamental dilemma that any form you take is going to cast a shadow. Confidence to some is arrogance to others, strength to one is weakness to another. Most of our behavior is neither bad nor good but dependent on the context.

And Jung argued that if you don't acknowledge your shadow-self, if you ignore it you will wind up projecting it on other people. Much much later Brene Brown would point out a finding of her grounded research that judgement is all about finding reassuringly worse examples in others of our own insecurities.

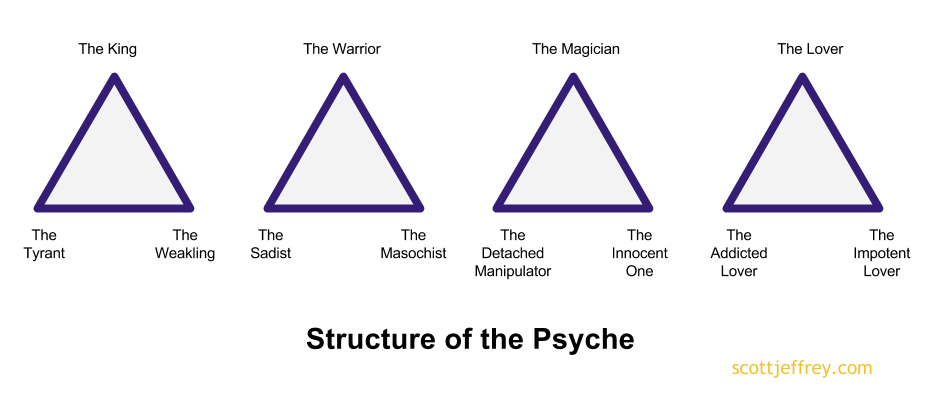

So it holds water, even as a simple metaphor. And I was exploring the idea that despite feeling I did a pretty good job of not repressing my darker self, I still had work to do. When I came across this offshoot of Jungian shadow-work:

And though I never dug down into the detail. As far as a checklist of archetypes goes I was able to go through and be like 'tyrant? got it, weakling? onto it. Sadism and masochism? I'm on that like white on rice... the innocent one???'

Now, I have no fucken idea what that specific archetype is. For all I know in the detail the innocence may be a feigning of innocence, a shady character that simply never takes responsibility. The hands-clean banker that never touches the product. But it was a catalyst for me.

It is a fact that part of the reason I see a psychologist, is because I need the authority of a qualified psychologist to reassure me that I'm not responsible for every bad thing that happens to me. A big part of this felt need is that I project innocence onto everyone. The people that prove obsticles to my achievement of more or less constant happiness are doing so not as malicious adults but as scared infants... they know not what they do. At the core of my being is an understanding that people are not against me, but for themselves.

I feel sympathy for some of the most powerful people in society doing en-masse damage to the most vulnerable and the environment which is the super-vulnerable future generations that need an environment to live in. I feel sympathy in the form of 'oh poor baby who hurt you.' To me Tony Abbott or Josh Frydenberg are just infants that need their dad's approval and love or something. I have to remind myself that they are also taking the money, the prestige, while hurting people. That's a conscious effort for me.

And yet the last person I think of as a scared innocent is myself. I repress that I don't know what I'm doing and that I'm largely incompetent. I feel that as the most conscious I have the most choice and the one with the most choice controls the system and whoever controls the system is ultimately responsible.

(Curiously, if you meet people who describe themselves as 'higher consciousness' it reliably predicts a person who will take almost no responsibility for anything ever.)

Another reason you may dislike Jungian Archetype's is Jordan Peterson, one of the most visible proponents of the value of archetypes. And JP is like drugs to me, only in so far as the people who are against him probably need to listen to him more and the people who are for him need to listen to him less. Just as the two extremes of the drug debate both need to move towards the middle.

One of the things I don't like about JP is what I perceive to be his overemphasis on Christian archetypes, but I have to concede in the greater run of psychoanalysis Greco-Roman pagan archetypes are very well represented, so it's kind of like complaining about all the black actors in Black Panther.

But one archetypal narrative that resonates with me from the Christian canon is the story of Saint George and the Dragon, which even Peterson in a round about way concedes is pre-dated by Babylonian God Marduk's battle with Tiamat. Probably because the events of Saint George and the Dragon didn't happen. The historical Saint George was a Roman soldier that refused to denounce his Christianity and was killed.

I have written before that I struggle with a White Knight complex, a chronic need to rescue, and this post isn't about that so there will be little exposition, but the traditional George and the Dragon story goes that this city has a lottery to sacrifice women to a local dragon, and the king's daughter comes up as the next sacrifice. The king offers to pay for a stand-in but no takers. So the princess is kicked outside the city walls to await devouring by the Dragon, and then Saint George happened along and offered to wait with her, then when the dragon shows up, makes the sign of the cross and kills it. With a bunch of variation.

To Christians, this story is metaphorical with the Dragon representing Sin and Wickedness and George represents purity and righteousness and virtue or something. But more broadly, you have the city that represents society/community/the known/safety. And you have the hero archetype who is someone who is willing to venture outside into the unknown and tame it.

The hero basically is someone living a high-risk, high-reward lifestyle. They expand the horizons of the community that by and large play it safe within the comfort of the city walls and the hero either dies and is celebrated, or lives and the king marries their daughter off to him.

My interest in this story was the disparity between my identifying with the hero-archetype (a stable secure life has no appeal to me, seems pointless) and not identifying. Specifically in that I wasn't looking for a princess to rescue, but a Saint Georgina. A compatriot, a counter part. And western narratives aren't rich with female hero archetypes (although history has a bunch, and it's kind of weird that Saint George is much more common iconography than Saint Jean de Arc, who did exist and whether there's a god or not, achieved much of what she is credited with).

Now, I was trying to pick apart this narrative for clues and at the time was noticing how much cultural appropriation Christianity did from pre-existing religious narratives. Especially in the Renaissance where the artists that created more or less 90% of Christian Iconography were cherry-picking Greek Paganism. Like we all picture 'Angels' as... let's face it, beautiful white people with wings. This is not how they are described in any Abrahamic source material, but it is how Cupid/Eros is depicted in Greek Mythology, and because that look is quite appealing as opposed to the monstrous thousand eyed beasts with bronze skin and 6 wings and faces of goats and other animals on the sides of their heads, so we have it.

And Saint George and the Dragon is probably a Christian wash of Jason and the Serpent. As in Jason and the Argonauts. Crucially, Jason achieved most of his tasks entirely dependent on his sorceress wife Medea, not some hapless princess tied to a post to be fed to a Dragon. And my story is much more similar to Jason and Medea than Saint George and nameless Princess.

This however is all preamble to the second piece of a puzzle, and that piece is called Hercules. Greek mythology had several central figures, not just Christ. But arguably the biggest is Hercules/Heracles. Here is a tragic figure that served as inspiration for the Stoics and the Cynics before them. Hercules life was suffering largely because the Goddess Hera unable to punish husband Zeus for infidelity naturally took it out on Hercules. Perhaps the most vindictive act was in adulthood driving Hercules mad so that he killed his wife and children.

Anyway, dig into Heracles sad story as you like, the point is that the Greek's celebrated Tragedies, and they had narratives of human suffering born of what I have taken to calling 'original innocence'. Greek Paganism is a legacy of European Culture and I find it interesting that in Greek mythology more often it was the God's betraying people, than people (like Adam and Eve) betraying God. Hercules was punished by the Gods not for what he'd done but who he was. He was the offspring of an unfaithful husband. Hera's wrath was misdirected.

Similarly the ordeals of Psyche, for whom Cupid/Eros fell for and was subsequently punished by Aphrodite/Venus. The Greek tragedies are populated not by people who were born and conceived of in Sin for breaking God's divine rule, but people who are basically good but punished by circumstance because the Gods are fickle, capricious and cruel.

And like Steven Fry, I too find the Pagan beliefs of the ancient Greeks do a much better job of explaining the chaotic and scary nature of the world than the Abrahamic Monotheism does.

But I want to switch to a different narrative now, to illustrate the importance of coming to know and believe in a concept like original innocence. And that is how people react to assertions that they are bad and full of sin.

Spoiler alert, but at the end of the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Jim gets his freedom. The emotional climax of the book though is Huck Finn coming to recognize that Jim the runaway slave is a human being with human emotions. It creates a huge dilemma for him, because Jim is property and the Christian Bible tells him that freeing someone else's property is a mortal sin.

Specifically this happens:

"I was a-trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself, "All right, then, I'll GO to hell."

We look back at history and think poor Huck was misguided. Surely freeing a slave rewards you with a place at the right hand of God, and keeping a slave sends you to hell. But that wasn't what Huck believed. Huck was from the south and taught that black people were basically chattel, beasts of burden. Freeing a slave was like stealing a cow, something specifically proscribed against in the 10 Commandments.

It is my experience that if you tell someone they are fundamentally bad, they embrace it. They,like Huck, damn themselves. It doesn't motivate people to become better. It fosters despair and resignation. Hercules undertook his 12 labors not because he was guilty, but because he was innocent. He sought redemption to return to himself, his fundamental conception of himself as basically good. Huck Finn was told he was no good all his life and to this assertion he returned. He is simply fortunate that he lived in a time and place where being bad could manifest itself as the greater good.

Some of the most important words ever muttered were 'There but for the grace of God goes John Bradford' though it's impossible to tell if this is a recognition of original sin/or innocence. I of course would interpret it as innocence believing that the universe is ultimately deterministic. Even people's choices are determined, and many thinkers including the original original sinner in Saint Augustine have bent their minds like pretzels trying to reconcile choice with concepts like predestination.

That mind bending process is to me, by and large a waste of time since I don't believe in an all powerful benevolent God. I just don't have the task of reconciling so I can be indifferent to problems of choice in the face of omniscience (someone who knows what choices we are going to make with our 'free' will).

Having attempted to give myself a cursory education in the history of philosophy, I find Kant's phrase "Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made." a huge improvement on the concept of original sin. To be honest I don't really get sin. But Kant appears to see us more usefully as something less than the pinacle of evolution: something perfectly adapted to it's environment and resilient to any possible environmental change. Rather we are a work in progress. Prototypes all, just trying our best. And like Hera, our environment may drive some of us mad, but not so mad as to be beyond redemption.

Because at one point, long ago, no matter what life had in store for us. We were innocent. To this nature we can return.

There's a minority of people alive at this time that like it or not have much of their thinking shaped by the ideas of Christianity. A lasting legacy of the death-bed conversion of Constantine the Great who himself lived almost his entire life as a pagan of questionable devotion.

But that's basically why, if you're of European descent, or descended from the collonized of the British. You know a lot about Christianity and very very little about say: Zoroastranism, or Pythagoreans... Constantine's offspring basically made it a legal requirement for European citizens to be Christian, something that wasn't really relaxed until the enlightenment though eased a little in the Renaissance.

But that's going too far forward. First you have Augustine who conceived of the idea of original sin, which was highly influential on Thomas Aquinas - and this became a shaper of thoughts of all the societies that trace lineage back to the Roman Empire.

Such that I, raised by non-believers, in a secular society give some credence to the idea that I was born broken, in deficit, indebted and need to do something in the course of my life to make myself whole. That I am under some obligation to do something with my good fortune because it was gifted to me and I am not worthy of it.

I'm sure this takes many manifestations, but to me original sin in the modern material world really manifests as the need to live up to our potential. To make the most of our opportunities. That if we rest on our haunches and simply say 'enough' then that makes a waste of our lives. It makes us bad people.

Now there's a place for religion in cultivating ourselves. And how I feel it should be navigated particularly by people like me, who cannot abide the bullshit of deriving moral authority from extraordinary claims, is another post. Richer in my experience are psychology - the understanding of the mind, and practical philosophy - what constitutes a good life.

Much of the work of clinical psychology is, I believe, having to deal with original sin. Specifically that children being egocentric in behavior, internalize and blame themselves for the dysfunctions of their caregivers. There are a lot of adults that believe they failed to make their parents happy, or they failed to save their parents marriage. And it is true some adults have a child in an attempt to save a marriage, or even more children to save a marriage, but the fault lies with that adult, not the child.

Again it's hard to draw distinct defined edges around concepts as fuzzy as religion, philosophy and psychology. They all feed into each other. But I once had a councilor break the therapeutic process down for me into two steps:

1. Look for Patterns.

2. Relieve Tension.

Let's look at that second part. Because it's a part that original sin can contribute to. What is the tension? The 'tension' most often is betwixt our conception of who we are supposed to be, and who we are. Incredibly productive people berate themselves for feeling tired, or taking breaks, or taking days off, or holidays etc. Nice people beat themselves up for viewing pornography. Devoted partners hate themselves for feeling attracted to people who aren't their partners.

There are ample opportunities to beat ourselves up for perceived flaws.

Hopefully you can relate to this notion of tension. Let's now turn to the notion of relieving it - Carl Rogers, one of the nicest people in the history of psychotherapy whom along with Maslow was one of the first to take psychotherapy from simply correcting for pathos (negative) psychology but look at trying to attain the pinnacle of psychological health.

Maslow called this pinnacle 'Self-actualization' the ability to be oneself. Rogers called it 'Congruence' basically a freedom from the psychological pain of cognitive dissonance. And perhaps earliest of all was Jung who called it 'Integration' specifically 'Integrating the shadow'.

Even then, there's an argument to be made that Nietzsche in the school of philosophy who said 'become what thou art' coined the notion of a pinnacle of psychological health. In turn perhaps owing that to Plato, fanboy of Socretes, to whom the unobserved life was not worth living.

I've digressed, let's get back to Jung. Jungian archetypes, 'Analytical Psychology' is I will admit, off-putting for most. It often descends into psychotherapuetic quackery. You wouldn't believe how many times I've been enjoying a youtube talk by a professional psychologist on shadow work and suddenly they start talking astrology and specific advice for star-signs like that's a perfectly reasonable given.

So if you dare to tread the archetypical road, expect deterrants in the form of outright idiocy. But the basic mechanics of Jung's concept of the Shadow are perfectly reasonable and functional, even independantly verifiable. Perhaps best captured in the sensible words of one of histories great level-headed imperfect human beings Abraham Lincoln 'You can please some people some of the time, and some people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can't please all of the people all of the time." and if you can't draw the connection, it's just a fundamental dilemma that any form you take is going to cast a shadow. Confidence to some is arrogance to others, strength to one is weakness to another. Most of our behavior is neither bad nor good but dependent on the context.

And Jung argued that if you don't acknowledge your shadow-self, if you ignore it you will wind up projecting it on other people. Much much later Brene Brown would point out a finding of her grounded research that judgement is all about finding reassuringly worse examples in others of our own insecurities.

So it holds water, even as a simple metaphor. And I was exploring the idea that despite feeling I did a pretty good job of not repressing my darker self, I still had work to do. When I came across this offshoot of Jungian shadow-work:

And though I never dug down into the detail. As far as a checklist of archetypes goes I was able to go through and be like 'tyrant? got it, weakling? onto it. Sadism and masochism? I'm on that like white on rice... the innocent one???'

Now, I have no fucken idea what that specific archetype is. For all I know in the detail the innocence may be a feigning of innocence, a shady character that simply never takes responsibility. The hands-clean banker that never touches the product. But it was a catalyst for me.

It is a fact that part of the reason I see a psychologist, is because I need the authority of a qualified psychologist to reassure me that I'm not responsible for every bad thing that happens to me. A big part of this felt need is that I project innocence onto everyone. The people that prove obsticles to my achievement of more or less constant happiness are doing so not as malicious adults but as scared infants... they know not what they do. At the core of my being is an understanding that people are not against me, but for themselves.

I feel sympathy for some of the most powerful people in society doing en-masse damage to the most vulnerable and the environment which is the super-vulnerable future generations that need an environment to live in. I feel sympathy in the form of 'oh poor baby who hurt you.' To me Tony Abbott or Josh Frydenberg are just infants that need their dad's approval and love or something. I have to remind myself that they are also taking the money, the prestige, while hurting people. That's a conscious effort for me.

And yet the last person I think of as a scared innocent is myself. I repress that I don't know what I'm doing and that I'm largely incompetent. I feel that as the most conscious I have the most choice and the one with the most choice controls the system and whoever controls the system is ultimately responsible.

(Curiously, if you meet people who describe themselves as 'higher consciousness' it reliably predicts a person who will take almost no responsibility for anything ever.)

Another reason you may dislike Jungian Archetype's is Jordan Peterson, one of the most visible proponents of the value of archetypes. And JP is like drugs to me, only in so far as the people who are against him probably need to listen to him more and the people who are for him need to listen to him less. Just as the two extremes of the drug debate both need to move towards the middle.

One of the things I don't like about JP is what I perceive to be his overemphasis on Christian archetypes, but I have to concede in the greater run of psychoanalysis Greco-Roman pagan archetypes are very well represented, so it's kind of like complaining about all the black actors in Black Panther.

But one archetypal narrative that resonates with me from the Christian canon is the story of Saint George and the Dragon, which even Peterson in a round about way concedes is pre-dated by Babylonian God Marduk's battle with Tiamat. Probably because the events of Saint George and the Dragon didn't happen. The historical Saint George was a Roman soldier that refused to denounce his Christianity and was killed.

I have written before that I struggle with a White Knight complex, a chronic need to rescue, and this post isn't about that so there will be little exposition, but the traditional George and the Dragon story goes that this city has a lottery to sacrifice women to a local dragon, and the king's daughter comes up as the next sacrifice. The king offers to pay for a stand-in but no takers. So the princess is kicked outside the city walls to await devouring by the Dragon, and then Saint George happened along and offered to wait with her, then when the dragon shows up, makes the sign of the cross and kills it. With a bunch of variation.

To Christians, this story is metaphorical with the Dragon representing Sin and Wickedness and George represents purity and righteousness and virtue or something. But more broadly, you have the city that represents society/community/the known/safety. And you have the hero archetype who is someone who is willing to venture outside into the unknown and tame it.

The hero basically is someone living a high-risk, high-reward lifestyle. They expand the horizons of the community that by and large play it safe within the comfort of the city walls and the hero either dies and is celebrated, or lives and the king marries their daughter off to him.

My interest in this story was the disparity between my identifying with the hero-archetype (a stable secure life has no appeal to me, seems pointless) and not identifying. Specifically in that I wasn't looking for a princess to rescue, but a Saint Georgina. A compatriot, a counter part. And western narratives aren't rich with female hero archetypes (although history has a bunch, and it's kind of weird that Saint George is much more common iconography than Saint Jean de Arc, who did exist and whether there's a god or not, achieved much of what she is credited with).

Now, I was trying to pick apart this narrative for clues and at the time was noticing how much cultural appropriation Christianity did from pre-existing religious narratives. Especially in the Renaissance where the artists that created more or less 90% of Christian Iconography were cherry-picking Greek Paganism. Like we all picture 'Angels' as... let's face it, beautiful white people with wings. This is not how they are described in any Abrahamic source material, but it is how Cupid/Eros is depicted in Greek Mythology, and because that look is quite appealing as opposed to the monstrous thousand eyed beasts with bronze skin and 6 wings and faces of goats and other animals on the sides of their heads, so we have it.

And Saint George and the Dragon is probably a Christian wash of Jason and the Serpent. As in Jason and the Argonauts. Crucially, Jason achieved most of his tasks entirely dependent on his sorceress wife Medea, not some hapless princess tied to a post to be fed to a Dragon. And my story is much more similar to Jason and Medea than Saint George and nameless Princess.

This however is all preamble to the second piece of a puzzle, and that piece is called Hercules. Greek mythology had several central figures, not just Christ. But arguably the biggest is Hercules/Heracles. Here is a tragic figure that served as inspiration for the Stoics and the Cynics before them. Hercules life was suffering largely because the Goddess Hera unable to punish husband Zeus for infidelity naturally took it out on Hercules. Perhaps the most vindictive act was in adulthood driving Hercules mad so that he killed his wife and children.

Anyway, dig into Heracles sad story as you like, the point is that the Greek's celebrated Tragedies, and they had narratives of human suffering born of what I have taken to calling 'original innocence'. Greek Paganism is a legacy of European Culture and I find it interesting that in Greek mythology more often it was the God's betraying people, than people (like Adam and Eve) betraying God. Hercules was punished by the Gods not for what he'd done but who he was. He was the offspring of an unfaithful husband. Hera's wrath was misdirected.

Similarly the ordeals of Psyche, for whom Cupid/Eros fell for and was subsequently punished by Aphrodite/Venus. The Greek tragedies are populated not by people who were born and conceived of in Sin for breaking God's divine rule, but people who are basically good but punished by circumstance because the Gods are fickle, capricious and cruel.

And like Steven Fry, I too find the Pagan beliefs of the ancient Greeks do a much better job of explaining the chaotic and scary nature of the world than the Abrahamic Monotheism does.

But I want to switch to a different narrative now, to illustrate the importance of coming to know and believe in a concept like original innocence. And that is how people react to assertions that they are bad and full of sin.

Spoiler alert, but at the end of the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Jim gets his freedom. The emotional climax of the book though is Huck Finn coming to recognize that Jim the runaway slave is a human being with human emotions. It creates a huge dilemma for him, because Jim is property and the Christian Bible tells him that freeing someone else's property is a mortal sin.

Specifically this happens:

"I was a-trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself, "All right, then, I'll GO to hell."

We look back at history and think poor Huck was misguided. Surely freeing a slave rewards you with a place at the right hand of God, and keeping a slave sends you to hell. But that wasn't what Huck believed. Huck was from the south and taught that black people were basically chattel, beasts of burden. Freeing a slave was like stealing a cow, something specifically proscribed against in the 10 Commandments.

It is my experience that if you tell someone they are fundamentally bad, they embrace it. They,like Huck, damn themselves. It doesn't motivate people to become better. It fosters despair and resignation. Hercules undertook his 12 labors not because he was guilty, but because he was innocent. He sought redemption to return to himself, his fundamental conception of himself as basically good. Huck Finn was told he was no good all his life and to this assertion he returned. He is simply fortunate that he lived in a time and place where being bad could manifest itself as the greater good.

Some of the most important words ever muttered were 'There but for the grace of God goes John Bradford' though it's impossible to tell if this is a recognition of original sin/or innocence. I of course would interpret it as innocence believing that the universe is ultimately deterministic. Even people's choices are determined, and many thinkers including the original original sinner in Saint Augustine have bent their minds like pretzels trying to reconcile choice with concepts like predestination.

That mind bending process is to me, by and large a waste of time since I don't believe in an all powerful benevolent God. I just don't have the task of reconciling so I can be indifferent to problems of choice in the face of omniscience (someone who knows what choices we are going to make with our 'free' will).

Having attempted to give myself a cursory education in the history of philosophy, I find Kant's phrase "Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made." a huge improvement on the concept of original sin. To be honest I don't really get sin. But Kant appears to see us more usefully as something less than the pinacle of evolution: something perfectly adapted to it's environment and resilient to any possible environmental change. Rather we are a work in progress. Prototypes all, just trying our best. And like Hera, our environment may drive some of us mad, but not so mad as to be beyond redemption.

Because at one point, long ago, no matter what life had in store for us. We were innocent. To this nature we can return.